Flax Fiber

Some of the oldest woven fibers in human history are linens derived from the stalks of flax plants. In Canada, flax producers, researchers, entrepreneurs and government have been working for years to develop a viable fiber industry. Progress is being made on several fronts.

The Fiber Inside Flax

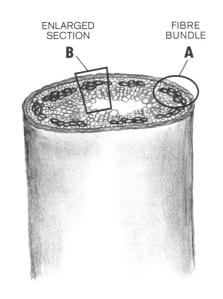

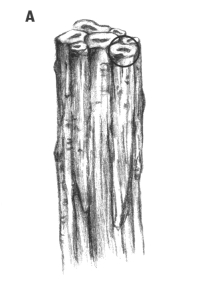

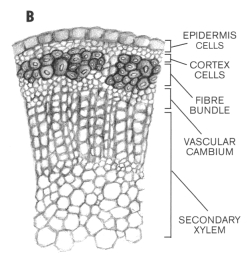

Physically, the fibers inside the stems of flax are actually bundles of tiny fibers called "ultimate fibers".

Physically, the fibers inside the stems of flax are actually bundles of tiny fibers called "ultimate fibers".

These ultimate fibers are roughly the diameter and length of cotton fibers, although flax fibers absorb about 50 per cent more moisture than cotton fibers. This means that garments made from flax fibers will feel cooler and drier than cotton garments, especially on hot, humid days.

Over 90 per cent of the world's spinning and weaving equipment is designed to used fibers with the approximate length and diameter of cotton fibers, while most synthetic fibers are extruded so they can easily be used in the cotton system of textile manufacturing.

This has led to the development of mechanical processes which attempt to break down flax fiber bundles into ultimate fibers to produce a flax-based fiber that could be spun on cotton equipment. Such flax is generally referred to as "cottonized flax".

In the past, the mechanical systems used to produce cottonized flax created large amounts of dust and waste fibers and could only use relatively expensive flax fibers that were properly retted. This meant that the cost of cottonized flax was considerably higher than cotton and had only limited demand in certain small markets.

In the past, the mechanical systems used to produce cottonized flax created large amounts of dust and waste fibers and could only use relatively expensive flax fibers that were properly retted. This meant that the cost of cottonized flax was considerably higher than cotton and had only limited demand in certain small markets.

However, researchers are looking at alternative ways to produce cottonized flax that minimizes the waste and produces a more consistent, lower cost fiber. Some methods include: the use of enzymes, flax hydrolysis and ultrasound. Breakthroughs have been made in all of these methods and costs are rapidly falling to the point where cottonized flax could compete with cotton fiber.

Processing

Processors of flax straw destined for specialty paper (such as cigarette paper) and lower end plastic composites (such as extrusion molded deck boards) use severe mechanical and/or chemical treatments to turn the flax straw into products they can use. These treatments are drastic but allow processors to buy flax straw that is free of plastic litter, relatively free of weeds, is within 50 miles of the processing facility, has reasonable fiber content and has reasonable height. These criteria are often easy for farmers to meet, without any extra effort, and hence farmers are often willing to sell their flax straw for token amounts ($5 to $10/tonne).

Medium value uses of flax fiber include:

- geotextiles

- insulation products

- absorbency products

- filtration products

- middle quality plastic composites

- low-end textiles

For these uses, processors need to produce flax fiber that: is almost totally free of shives (shives are the non-fiber part of the stems), has relatively consistent fineness (fiber diameters), has relatively consistent length, and is reasonably strong. These requirements, in turn, mean that the straw that is collected and processed must have fairly consistent length, stem diameters, reasonable fiber content (greater than 12% to 15%) and be partly or totally retted. Negative and/or unacceptable characteristics would include the presence of plastic litter, and abundance of weed seeds or stalks, short pieces of straw, the presence of seeds or seed holders, and far distant locations of fields. Payment for such straw, could, in theory be in the range of $30 to $100 per tonne depending on the actual level of the various desirable fiber properties.

High end uses of flax fiber include:

- high-end plastic composites

- many textile applications

For these uses, processors need to produce flax fiber that is totally free of shives, can be finely divided, has good strength and has a consistent length distribution. The requirements, in turn, mean that the straw that is processed must be consistent in length, stem diameter, fiber content and degree of retting. It also means that the straw must be quite well retted so that the fiber bundles can be finely divided. Negative and/or unacceptable characteristics would include unretted straw, the presence of plastic litter, and abundance of weed seeds or stalks, short pieces of straw, the presence of seeds or seed holders, and far distant locations of fields. Payment for such straw, could, in theory be in the range of $60 to $150 per tonne depending on the actual level of the various desirable fiber properties.

The production of higher quality straw for higher quality fiber also results in a by-product: shives that can be sold into higher end markets. This, in turn, creates further opportunities for value adding industries and permits processors to pay even more for higher quality flax straw.